National security leaders rarely get to choose what to care about and how much to care about it. They are more often subjects of circumstances beyond their control. The September 11 attacks reversed the George W. Bush administration’s plan to reduce the United States’ global commitments and responsibilities. Revolutions across the Arab world pushed President Barack Obama back into the Middle East just as he was trying to pull America out. And Russia’s invasion of Ukraine upended the Biden administration’s goal of establishing “stable and predictable” relations with Moscow so that it could focus on strategic competition with China.

Policymakers could foresee many of the underlying forces and trends driving these agenda-shaping events. Yet, for the most part, they failed to plan for the most challenging manifestations of where these forces would lead. They had to scramble to reconceptualize and recalibrate their strategies to respond to unfolding events.

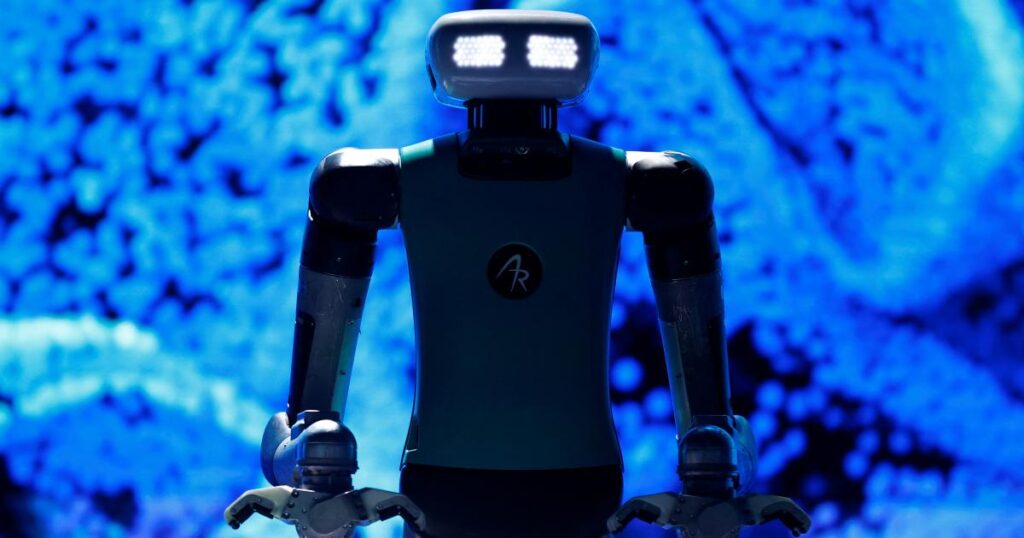

The rapid advance of artificial intelligence—and the possible emergence of artificial general intelligence—promises to present policymakers with even greater disruption. Indicators of a coming powerful change are everywhere. Beijing and Washington have made global AI leadership a strategic imperative, and leading U.S. and Chinese companies are racing to achieve AGI. News coverage features near-daily announcements of technical breakthroughs, discussions of AI-driven job loss, and fears of catastrophic global risks like the AI-enabled engineering of a deadly pandemic.

There is no way of knowing with certainty the exact trajectory along which AI will develop or precisely how it will transform national security. Policymakers should therefore assess and debate the merits of competing AI strategies with humility and caution. Whether one is bullish or bearish about AI’s prospects, though, national security leaders need to be ready to adapt their strategic plans to respond to events that could impose themselves on decision-makers this decade, if not during this presidential term. Washington must prepare for potential policy tradeoffs and geopolitical shifts, and identify practical steps it can take today to mitigate risks and turbocharge U.S. competitiveness. Some ideas and initiatives that today may seem infeasible or unnecessary will seem urgent and self-evident with the benefit of hindsight.

THINKING OUTSIDE THE BOX

There is no standard, shared definition of AGI or consensus on whether, when, or how it might emerge. Today’s frontier AI models are already increasingly capable of performing a greater number and complexity of cognitive tasks than the most skilled and best resourced humans. Since ChatGPT launched in 2022, the power of AI has increased by leaps and bounds. It is reasonable to assume that these models will become more powerful, autonomous, and diffuse in the coming years.

Nevertheless, the AGI era is not likely to announce itself with an earth-shattering moment like the nuclear era did with the first nuclear weapons test. Nor are the economic and technological circumstances as favorable to U.S. planners as they were in the past. In the nuclear era, for example, the U.S. government controlled the new technology, and planners had two decades to develop policy frameworks before a nuclear rival emerged. Planners today, by contrast, have less agency and time to adapt. China is already a near-peer in technology, a handful of private companies are steering development, and AI is a general-purpose technology that is spreading to nearly every part of the economy and society.

In this rapidly changing environment, national security leaders should dedicate scarce planning resources to plausible but acutely challenging events. These types of events are not merely disruptions to the status quo but also signposts of alternative futures.

Say, for instance, that a U.S. company claims to have made the transformative technological leap to AGI. Leaders must decide how the U.S. government should respond if the company requests to be treated as a “national security asset.” This designation would grant the company public support that could allow it to secure its facilities, access sensitive or proprietary data, acquire more advanced chips, and avoid certain regulations. Alternatively, a Chinese firm may declare that it has achieved AGI before any of its U.S. rivals.

Planning for AGI cannot be delegated to futurists sent to a far-off bunker.

Policymakers grappling with these scenarios will have to balance competing and sometimes contradictory assessments, which will lead to different judgments about how much risk to accept and which concerns to prioritize. Without robust, independent analytic capabilities, the U.S. government may struggle to determine whether the firms’ claims are credible. National security leaders will also have to consider whether the new technological advance could provide China with a strategic advantage. If they fear AGI could give Beijing the ability to identify and exploit vulnerabilities in U.S. critical infrastructure faster than cyberdefenses can patch them, for example, they may prescribe actions—like trying to slow or sabotage China’s AI development—that could escalate the risk of geopolitical conflict. On the other hand, if national security leaders are more concerned that nonstate actors or terrorists could use this new technology to create catastrophic bioweapons, they may prefer to try to cooperate with Beijing to prevent proliferation of a larger global threat.

Enhancing preparedness for AGI scenarios requires better understanding of the AI ecosystem at home and abroad. Government agencies need to keep up with how AI is developing to identify where new advances are most likely to emerge. This will reduce the risk of strategic surprise and help inform policy choices on which bottlenecks to prioritize and which vulnerabilities to exploit to potentially slow China’s progress.

Policymakers also need to explore ways to work with the private sector and with other countries. A scalable, dynamic, and two-way private-public partnership is crucial for a strategic response to the current challenges that AI presents, and this will be even more the case in an AGI world. Mutual suspicion between government and the private sector could cripple any crisis response. Meanwhile, leaders will need to develop policies to share sensitive, proprietary information on developments in frontier AI with partners and allies. Without such policies, it will be challenging to build the international coalition needed to respond to an AI-induced crisis, reduce global risk, and hold countries and companies accountable for irresponsible behavior.

ADVERSARIAL INTELLIGENCE

Artificial general intelligence will not only complicate existing geopolitical dynamics; it will also present novel national security challenges. Imagine an unprecedented AI-enabled cyberattack that wreaks havoc on financial institutions, private corporations, and government agencies and shuts down physical systems ranging from critical infrastructure to industrial robotics. In today’s world, determining who is responsible for cyberwarfare is already a challenging and time-intensive task. Any number of state and nonstate actors possess both the means and motivations to carry out destabilizing attacks. In a world with increasingly advanced AI, however, the situation would be even more complex. Policymakers would have to contemplate not only the possibility that an operation of this scale might be the prelude to a military campaign but also that it might be the work of an autonomous, self-replicating AI agent.

Planning for this scenario requires evaluating how today’s capabilities can handle tomorrow’s challenges. Governments cannot rely on present-day tools and techniques to quickly and confidently assess a threat, let alone apply relevant countermeasures. Given AI systems’ proven capacity to deceive and dissemble, current systems may be unable to determine whether an AI agent is operating on its own or at the behest of an adversary. Planners need to find new ways to assess its motivations and how to deter escalation.

Preparing for the worst requires reevaluating “attribution agnostic” steps to harden cyberdefenses, isolate potentially compromised data centers, and prevent the incapacitation of drones or connected vehicles. Planners need to assess whether current military and continuity of operations protocols can handle threats from adversarial AI. Public distrust of the government and technology companies will make it even more difficult to reassure a worried populace in the event of artificial intelligence–fueled misinformation. Given that an autonomous AI agent is not likely to respect national boundaries, adequate preparations would involve setting up channels with partners and adversaries alike to coordinate an effective international response.

How leaders diagnose the external impacts of an impending threat will shape how they react. In the event of a cyberattack, policymakers will have to make a real-time decision about whether to pursue targeted shutdowns of vulnerable cyber-physical systems and compromised data centers or—fearing the potential for rapid replication—impose a more comprehensive shutdown, which could prevent escalation but inhibit the functioning of the digital economy and systems on which airports and power plants rely. This loss-of-control scenario highlights the importance of clarifying legal authority and developing incident-response plans. More broadly, it reinforces the urgency of creating policies and technical strategies to address how advanced models are inclined to misbehave.

At minimum, planning should involve four types of actions. First, it should establish “no regret” actions that policymakers and private-sector players can take today to respond to events from a position of strength. Second, it should create “break glass” playbooks for future emergencies that can be continually updated as new threats, opportunities, and concepts emerge. Third, it should invest in capabilities that seem crucial across multiple scenarios. Finally, it should prioritize early indicators and warnings of strategic failure and create conditions for course corrections.

NO COUNTRY FOR OLD HABITS

Planning for the impacts of AGI on national security needs to start now. In an increasingly competitive and combustible world, and with an economically fragile and politically polarized domestic environment, the United States cannot afford being caught by surprise.

Although it is possible that AI will ultimately prove to be a “normal technology”—a technology, like the Internet or electricity, that transforms the world but whose pace of adoption has natural limits that governments and societies can control—it would be foolish to assume that preparing for major disruption would be a mistake. Planning for more difficult challenges can help leaders identify core strategic issues and build response tools that will be equally useful in less severe circumstances. It would also be unwise to presume that such planning will generate policy instincts and pathways that exacerbate risks or slow AI advances. In the nuclear era, for example, planning for potential nuclear terrorism inspired global initiatives to secure the fissile material needed to make nuclear weapons that ultimately made the world safer.

It would also be dangerous to treat the possibility of AGI like any “normal scenario” in the national security world. Technological expertise and fluency across the government is limited and uneven, and the institutional players that would be involved in responding to any scenario extend far beyond traditional national security agencies. Most scenarios are likely to occur abroad and at home simultaneously. Any response will rely heavily on the choices and decisions of actors outside government, including companies and civil society organizations, that do not have a seat in the White House Situation Room and may not prioritize national security. Likewise, planning cannot be delegated to futurists and technical experts sent to a far-off bunker to spend months crafting detailed plans in isolation. Preparing for a future with AGI must continuously inform today’s strategic debates.

There is an active debate about the merits of various strategies to win the competition for AI while avoiding catastrophe, but there has been less discussion about how AGI might reshape the international landscape, the distribution of global power, and geopolitical alliances. In an increasingly multipolar world, emerging players see advanced AI—and how the United States and China diffuse AI technology and its underlying digital architecture—as key to their national aspirations. Early planning, tabletop exercises with allies and partners, and sustained dialogue with countries that want to hedge their diplomatic bets will ensure that strategic choices are mutually beneficial. Any AI strategy that fails to account for a multipolar world and a more distributed global technology ecosystem will fail. And any national security strategy that fails to grapple with the potentially transformative effects of AGI will become irrelevant.

National security leaders don’t get to choose their crises. They do, however, get to choose what to plan for and where to allocate resources to prepare for future challenges. Planning for AGI is not an indulgence in science fiction or a distraction from existing problems and opportunities. It is a responsible way to prepare for the very real possibility of a new set of national security challenges in a radically transformed world.

Loading…