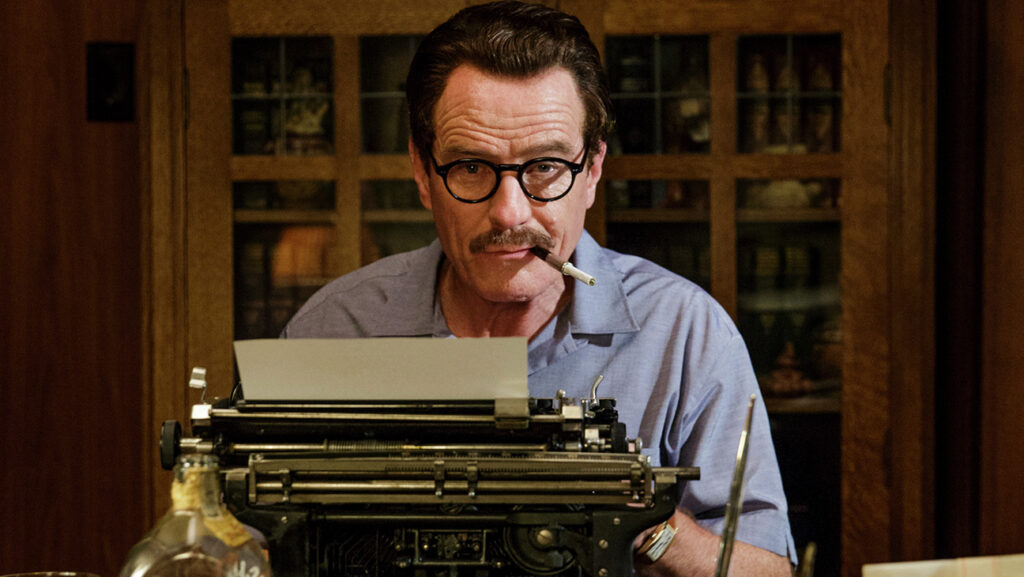

In 1953, Roman Holiday won the Oscar for best screenplay. The statue went to Ian McLellan Hunter. The man who actually wrote it, Dalton Trumbo, was blacklisted and invisible. It would take decades for the Academy to correct the record and attach his name to the film he wrote in exile.

It wasn’t an isolated case.

In 1939, The Wizard of Oz opened with Victor Fleming’s name on the director’s slate. But at least two other directors, George Cukor and King Vidor, had shaped the film’s tone and look. They were reassigned, dismissed, or absorbed into the machinery of the studio system — their fingerprints all over the work but absent from the billing block.

Poltergeist (1982) was widely assumed to be directed by Tobe Hooper. But ask anyone who worked on it, and you’ll hear another name: Steven Spielberg. His uncredited influence shaped the film’s aesthetic and editorial decisions, to the point that the line between oversight and authorship blurred entirely.

Hollywood, in other words, has always run on invisible labor. The screen may suggest singular genius. But behind every auteur is a crowd: collaborators, consultants, fixers, ghosts. Writers who never got the rewrite fee. Editors who salvaged a broken second act. Designers whose mood boards made the pitch deck sing.

Cinema is a collaborative art form. It always has been. But the myth of the lone genius — the one voice and the one vision — sells better. It flatters the director. It simplifies the awards campaign. It is a story the industry tells about itself.

And now that story has a new character. Not a ghostwriter. Not a blacklisted screenwriter. Something even quieter.

AI.

At first glance, it looks like the perfect creative partner. It doesn’t eat lunch. It doesn’t take notes. It doesn’t ask for credit. It can spit out three loglines in under a minute or draft a beat sheet before breakfast. For overworked executives and shrinking development teams, generative AI promises efficiency. For creatives, it presents something more unsettling.

Writers, producers and directors across the United States and the United Kingdom are already seeing the shift. Those I work with describe being handed machine-generated materials — character breakdowns, first drafts, pitch outlines — then being asked to develop them into something usable. One of my clients, a showrunner with multiple global hits, was recently asked to rewrite a pilot generated by ChatGPT. The terms were explicit. No credit. No disclosure. Just a polish pass — then back to the shadows.

Another, a designer on a high-budget science fiction project, found herself building the visual identity for a show whose original lookbook had been generated by Midjourney. Her job wasn’t to create, but to refine. The conceptual authorship had already been stripped and anonymized by an algorithm. The technology may be new. The playbook is not.

During the McCarthy era, entire productions relied on pseudonyms and stand-ins to get scripts by blacklisted writers onto the screen. Studios knew it. Agents knew it. Everyone knew it. And they went along with the lie because it made the product possible. It was plausible deniability dressed as process.

Today, it is not political ideology that drives invisibility. It is convenience. Generative tools let studios pretend that fewer people are involved. Fewer names to credit. Fewer residuals to pay. The assistant becomes the final pass. The designer becomes a prompt operator. The writer becomes the person who just helped out.

Streaming platforms have only accelerated this erosion of visibility. In the name of user experience, they have truncated title sequences, eliminated credit scrolls and hidden production information behind menus no casual viewer will ever click through. In many cases, the audience never sees who made what — and that, increasingly, feels like the point.

This is not technophobia. It is memory. Credit is how we record history — who touched the work, who shaped the story. Strip the names away, and the work loses its lineage. The line between human and machine begins to blur. Not because the machine is so smart, but because we stopped pointing to the people.

Christopher Nolan made Oppenheimer with hardly a pixel of AI. That might read as stubborn. Or it might serve as a reminder. Real authorship still exists. But it takes effort. It costs more. And it isn’t frictionless.

The industry will tell you AI is just a tool. That it is a shortcut. A sketchpad. A helper. But tools do not lobby for credits. Tools do not get residuals. Tools do not speak up when their work is misused. People do.

And if those people are replaced, or folded into the shadows, or quietly cut out of the process, we are not looking at evolution. We are looking at erasure.

Studios have always known how to simplify credit. That is what the auteur myth was built for — to turn a cacophony of effort into a single, salable signature. Now AI allows them to do it at scale. Without negotiation. Without names. Without cost.

It is not collaboration. It is erasure disguised as efficiency.

If we let that lie go unchallenged — if we stop asking who really made the thing — we will not just lose the labor. We will lose the lineage. The accountability. The soul.

So stay through the credits. Watch the names. Count them. Because when they stop scrolling, the silence that follows won’t signal innovation. It will mark extinction.